Today is the publication date of the non-fiction tome Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher by A. Brad Schwartz and myself. I am celebrating this by giving away ten copies.

[Edit: All copies have been claimed. Thank you!]

The four Eliot Ness novels covering his Cleveland years – a quartet that eventually led to both the play/film Eliot Ness: An Untouchable Life and the two non-fiction works, Scarface and the Untouchable and the new Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher – are available at Amazon from Wolfpack as An Eliot Ness Mystery Omnibus for $2.99. Even with my meager math skills, I can tell that’s a penny under three bucks for four novels.

While we hope to offer new print versions of the novels (perhaps in two-novels-to-a-volume form), right now they are Kindle e-books only. So no giveaways are in the cards for now. But if you have already read the novels – any of them – and liked them, reviews of the Eliot Ness Omnibus would be much appreciated. Right now we have a paltry two reviews at Amazon and that doesn’t go very far at getting the Omnibus noticed. Even if you haven’t bought the books in this new form, don’t hesitate about reviewing them under the Omnibus listing.

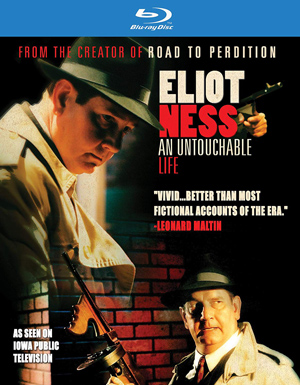

Since I’ll be talking about Eliot Ness this week, I’ll remind you that Eliot Ness: An Untouchable Life is available on Blu-ray now at Amazon.

It’s also available on DVD for $9.99.

Reviews for Untouchable Life at Amazon are also appreciated. We only have two at the moment, and no one has specifically talked about the Blu-ray.

Also, the entire five-book Mallory series will be available for 99-cents each as Mystery, Thriller & Suspense Kindle book deals from now through the end of August. Included in the sale will be the thriller Regeneration by Barb and me (as “Barbara Allan”), also at 99-cents.

The Mallory titles are: No Cure for Death; The Baby Blue Rip-off; Kill Your Darlings; A Shroud for Aquarius; and Nice Weekend for a Murder.

Is it undignified to celebrate the career of a law enforcement icon who could not be bribed by offering a giveaway, and hawking various titles pertaining to him? I don’t really care, since I never claimed to be untouchable myself.

But Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher (it has a subtitle but I decline to use it, because I dislike it intensely) marks the final stage of an interest in the real-life lawman that reaches back into my childhood. My interest in such things begins even before the first Untouchables of two installments on Desilu Playhouse aired on April 20, 1959. The Dick Tracy comic strip (by way of comic book reprints) had ignited that interest; but, in fairness, since Ness was the real-life basis of Chester Gould’s Tracy, the Untouchable was already in the mix.

There’s no question that Tracy and Ness got me interested in stories about detectives, but more significantly The Untouchables TV series (and the autobiographical book that spawned it) got me interested in the factual material that generated so much of the guns-and-gangster pulp fiction I adored. My novel True Detective (1983), after all, deals with the same crime – the assassination of Mayor Cermak – as a two-part Untouchables episode I saw as a kid. Granted, that two-parter only nodded at history, but that nod was enough to get my attention.

Ness became the Pat Chambers to Nathan Heller’s Mike Hammer in a number of the Heller novels. At the request of an editor at Bantam, I spun Ness off into the four novels that dealt with his Cleveland years (previously explored, somewhat inaccurately, in Oscar Fraley’s Untouchables follow-up, Four Against the Mob, but otherwise little written about).

Two things are, I think, significant about those novels, including that they represent the first time actual cases of this real-life American detective had been the basis of stories about him (excluding the initial two-part telefilm). More importantly, the writing of the books led to research by myself and George Hagenauer that uncovered new (or at least forgotten) information about Ness.

In addition to his occasional role in the Nathan Heller saga, Ness appeared in my graphic novel Road to Perdition (drawn by the great Richard Piers Rayner) and in my prose sequel, Road to Purgatory (available from Brash Books). The latter, to some degree, dealt with Ness’s little-known role in fighting venereal disease on military bases and elsewhere during World War II.

For unknown reasons, Ness was not depicted in the film version of Road to Perdition, but that nonetheless led to the play (and 2007 video production of) Eliot Ness: An Untouchable Life. Initially, actor Michael Cornelison and I were planning to do a one-man show about Perdition antagonist John Looney. We intended to mount it in Rock Island (where Looney had been the local crime boss in the early Twentieth Century) and shoot the film in one of the two existing houses were Looney had lived.

Somewhere along the line, one of us – it may have been Mike – suggested that Ness would have greater appeal to a wider national audience. Also, over the years I had heard from editors and readers that I should do a non-fiction treatment of Ness, since I had done so much research into and about him. Much of what George and I uncovered about Ness was making its way into the accounts of non-fiction writers (fiction writers, too) without credit.

As an independent filmmaker, looking for productions that could be produced cheaply but well, I found a one-man show appealing. I also had the possibility of a grant from Humanities Iowa, for whom I’d made an appearance at a University of Iowa event with editorial cartoonist, Paul Conrad. We mounted the play at the Des Moines Playhouse, where we shot the film between performances. My eventual co-author Brad Schwartz saw the play and that sparked our collaboration.

I had intended An Untouchable Life to be my final statement on Ness. While it is written from Ness’s point of view, skewed to his own memories and perceptions of his life, and some dramatic liberties were taken (by both Ness and me!), the play represents the most accurate depiction of Ness on screen to date.

Eventually, however, Brad convinced me to join him in writing the definitive biography of Ness. We embarked on doing that only to discover another, apparently major Ness biography was about to come out. I had once considered doing a massive, Godfather-style novel on both Capone and Ness, cutting back and forth between their stories. Now I suggested we follow that approach, but in a strictly non-fiction fashion. That would set us apart from any Ness bio or Capone bio, for that matter.

Obviously that approach – particularly since we intended to do cradle-to-grave accounts of both men – turned out to be too big for one book. Now we have a two-volume work that I feel confident is the definite treatment of the life of Eliot Ness. The research George and I did for the novels has been greatly enhanced by further research, much of it by my co-author, who crisscrossed the country in his efforts, even talking to surviving friends and associates of the long-deceased lawman.

It must be said that I have written about several different Eliot Nesses. The Ness of the Heller books serves a specific function – he is Heller’s conscience, the Jiminy Cricket to his Pinocchio. The portrayal darkens in Angel in Black and Do No Harm. The Eliot Ness Omnibus of Cleveland novels is a basically accurate but somewhat romanticized version of Ness – far closer to reality than Robert Stack, but splitting the difference between them. The same is true of Ness in Road to Perdition and Road to Purgatory. Eliot Ness: An Untouchable Life is only slightly romanticized, and (in my view at least) portrays him as he saw himself.

The real Ness can be found in Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher (and Scarface and the Untouchable). My co-author and I did not always agree on what – or who – the research added up to. We wrestled our way into a joint presentation that is probably more accurate than if either of us had been turned loose alone.

I can look at these two works and feel that, at last, I have done right by this complex real-life Dick Tracy. With the publication of Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher, with the recent publication of Do No Harm (which ends Ness’s story in the world of Nate Heller), and with the four Ness-in-Cleveland novels gathered into Omnibus form, I feel I’ve come full circle.

Here’s a great Wall Street Journal review. Here is the link, but it requires a subscription to read.

After helping to put Al Capone behind bars, lawman Eliot Ness came to Cleveland, where he did battle with a vicious killer.

Moviegoers of a certain age will remember Eliot Ness—the upright law-enforcement figure who battled corruption and organized crime from the 1920s to the ’40s—as portrayed by a tough-talking Kevin Costner in Brian De Palma’s 1987 movie “The Untouchables.” Television viewers from an even earlier era will recall Ness depicted by the stern-faced Robert Stack in the ABC series (1959-63) of the same name. But the real-life Ness, as revealed in Max Allan Collins and A. Brad Schwartz’s “Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher,” was less the hard-boiled hero of popular culture than a humane and forward-thinking lawman as interested in preventing crime as in punishing it.

The Chicago-born Ness (1903-57) came to prominence as a Prohibition agent in the Windy City, doing battle with Al Capone and other bootleggers as head of his own hand-picked squad of agents. His men were dubbed the “Untouchables” for their refusal to accept payoffs or gratuities. As a friend observed of the incorruptible lawman: “Honesty amounted to almost a fetish.”

The government put Capone behind bars in 1932 via the prosecution of a tax-evasion case, but the work of Ness and his men was central to establishing the extent of the mobster’s criminal activities. With Capone out of the picture, the Untouchables were disbanded, and Prohibition ended soon after. Ness, a nationally known figure (his physical and professional image inspired Chester Gould’s comic-strip police hero Dick Tracy), looked beyond Chicago for new opportunity. He found it in Cleveland, the site of his next significant successes—but also of the disturbing case that gives Messrs. Collins and Schwartz’s book its title.

Ness was named Cleveland’s director of public safety in 1935 and was put in charge of the city’s police and fire departments. He found the cops to be sloppy, uncooperative and demoralized. Once more he formed his own discrete unit of Untouchables to weed out incompetent and corrupt officers and hire smart new ones. “Intelligence,” he counseled, “must supplant brutality.”

But even Ness was stumped trying to apprehend the “torso murderer” responsible for a series of ghoulish killings, in which parts of dismembered and beheaded corpses were strewn about the woods and dumpsites of Kingsbury Run, one of the city’s poorest areas. “The mystery of the headless dead” drew national and international attention. In Germany, the Nazi press mocked America’s inability to apprehend the “Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.” With no witnesses and sometimes no way even to identify victims—and with advanced forensics techniques far in the future—police were stymied.

By 1938, the authors write, “the Butcher had become the subject of the largest manhunt in Cleveland’s history.” Thousands of citizens wrote and called the cops with worthless tips. “The investigators, after years of fruitless searching, grew desperate, pursuing ever more eccentric lines of inquiry.” At last a few tantalizing leads brought an alcoholic and mentally disturbed doctor named Francis Sweeney to the attention of the detectives.

Ness and his crew subjected the 44-year-old Sweeney—who had shown signs of psychosis and had been verbally and physically cruel—to judicially inadmissible polygraph examinations that convinced all present of his guilt. Still, despite an abundance of circumstantial indicators, Ness had no hard evidence. Complicating matters was the man’s being a cousin of a local congressman, a vocal Ness critic. Prosecution was not an option. Ness handled the matter privately, helping to arrange Sweeney’s commitment to a mental hospital. Sweeney, who was institutionalized for much of the rest of his life, sent a series of bizarre and taunting postcards to Ness through the mid-1950s.

Though Ness was sure that the killer had been caught and dealt with, he couldn’t officially close the case and so swore himself and his men to secrecy. The public was left with the impression that the culprit might still be at large. The case of the Mad Butcher, with its unsatisfying non-finale, fits a bit awkwardly into Messrs. Collins and Schwartz’s wider narrative. In the latter stages of their book, the authors ably follow Ness through an unsuccessful foray into city politics and a disappointing business career. But given this work’s title and its subtitle—“Hunting America’s Deadliest Unidentified Serial Killer at the Dawn of Modern Criminology”—one sometimes gets the feeling of two different books uneasily hitched.

That said, the authors have done Ness justice. It’s discouraging to learn that a man who refused a fortune in bribes died $9,000 in debt. Shortly before his fatal heart attack at the age of 54, he finished work on the memoir that would revive and romanticize his reputation and bring his third wife and their adopted son a modicum of income.

Messrs. Collins and Schwartz, in this, their second deeply researched book about Ness, don’t gloss over their subject’s failings and blind spots, but they do show that he tried harder than many to leave the world a better place. His “signature achievements in Cleveland—fighting juvenile delinquency, reorganizing the police department, promoting traffic safety—stemmed from a deep well of humanity and compassion,” they write. Now more than ever, the authors conclude, Ness’s name “should remind us of the rigorous standards he brought to law enforcement—professionalism, competence, honor, and decency—and a determination to make everyone safer by addressing the systemic root causes of crime.”

Review by Tom Nolan.

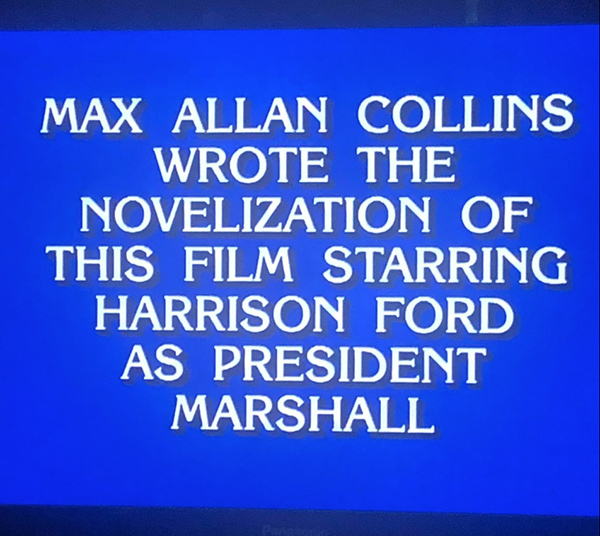

My favorite Jeopardy! question popped up again on a rerun this week:

Here’s a great interview with my buddy Charles Ardai, editor of Hard Case Crime. He mentions me several times, bless him.

Check out this wonderful review of The First Quarry.

M.A.C.