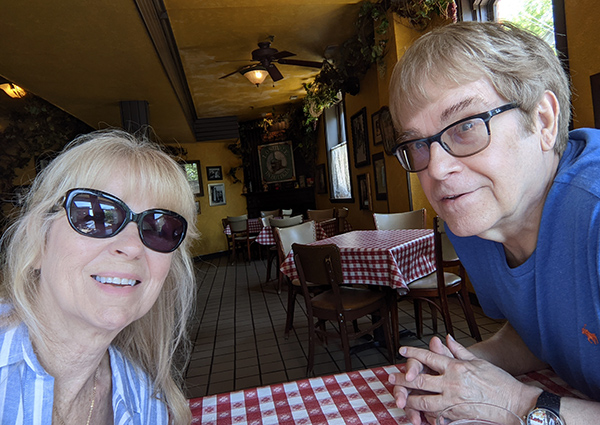

Crusin’ at Proof Social, l to r, M.A.C., Steve Kundel, Bill Anson, Scott Anson

The gig Saturday, July 3, at Proof Social in Muscatine went very well, especially considering it had been two years since Crusin’s last outing.

This was the first public performance with bass player Scott Anson (our guitar player Bill’s son). Scott filled in for Brian Van Winkle at the last performance – a private function in 2019 – before Covid sidelined us and everybody. He is a terrific bass player and a real asset to the band. Of course, it was bittersweet without Brian, whose premature, unexpected passing remains hard to accept.

We had a number of my fellow classmates of ‘66 Muscatine High School grads who came out for a kind of unofficial 55th reunion. But the performance on the patio outside the club (the same patio where we performed a number of times in past years for the Second Sunday concert series) enjoyed both nice weather and a standing room only crowd reflecting a broad demographic. My old pal from early Crusin’ days, Charlie Koenigsaecker, brought a group down from Iowa City. Charlie ran sound for us for back in the day and is a popular dj with great taste in addition to working at the Iowa City Library.

Another old friend, Doug Kreiger, came up to me and – once we’d kidded each other for a while – thanked me quite sincerely for all the music and stories I’d shared with my hometown (and beyond) over the years. It was a nice moment and an unexpected expression of sentiment.

I do find myself reflecting on all the years of music, knowing that the road ahead is limited in that regard whereas storytelling is less so. The loading in and out – as I mentioned last time – is so onerous that it calls into question whether or not it’s worth the effort. The day after, as I write this, I feel like I was hit by a truck. That was always the case after a band job, for the last three decades anyway, but now it feels like a bigger truck.

Gigs are unpredictable, always, and after a nice evening with weather cooperating, darkness fell and bugs attracted to the lights illuminating the band swarmed us, like Pappy Yokum getting assaulted by hordes of locusts as he tried to protect the turnip crop. These were tiny bugs, unidentifiable but similar to gnats, though they weren’t biting, just turning my keyboards into a gummy, sticky runway and clinging to my exposed flesh the same way. This didn’t happen till the last set, toward the end, and we limped through fifteen minutes of absolute insect invasion…and toward the end the notorious “fish bugs” joined the assault. They tell me fish bugs have only a 34-hour life span, and that’s way too long.

I’ve played in bands since 1965, frequently out of doors, and never had this happen before. And today I spent an hour cleaning the two keyboards of crushed bug carcasses, also a new experience.

Did God send the little devils to tell me I’d been doing this long enough?

On our recent trip to Minnesota for a family reunion, which centered around the graveside service of Barb’s mom, Barb and I went to a movie in Minneapolis. And I think I may be seriously out of step. I felt the same way this evening when I watched a movie on HBO Max.

In Minneapolis, we went to F9, as it’s being called, and it’s an appropriate title if “F” stands for what it should. I am easy to please with dumb action movies, and have seen every Fast and Furious movie in a theater and had fun. This one is sloppy and stupid, lacking both the Rock and Jason Stratham, but it did mark Barb and me officially getting back in the moviegoing swing – by walking out.

I didn’t walk out on director Steven Soderbergh’s No Sudden Move, with a cast so star-studded Matt Damon didn’t bother with getting a billing. But the only reason I didn’t walk out was because I was home. It’s a mess, incomprehensible and pretentious and frequently shot with distorting lenses that call attention to themselves. The great Don Cheadle spends the running time looking like he wished somebody had shown him the script. But the critics love it, so I am probably wrong.

F9 puts me out of step with the public and No Sudden Move puts me out of step with the critics. I’ve got all the bases covered!

Here’s a great review of Two for the Money (mostly about Bait Money but also the Nolan series in general).

And here’s a spiffy review of both novels collected in Double Down (Fly Paper and Hush Money).

Finally, here’s another Two for the Money review, generally not bad, but apparently the 22 year-old me in the early ‘70s was supposed to have better attitudes than “cringingly archaic” ones about women’s looks and tough guy prowess. You’d think I’d been writing a paperback crime novel with an early ‘70s mostly male readership in mind.

M.A.C.